Two guest blog posts were commissioned following the Performance Philosophy workshop “On Attention” held at Independent Dance in November 2019 as part of the Fellowship. The first was written a series of reflections on the workshop by choreographer, Adesola Akinleye from a participant perspective. This second post is a reflection by philosopher Wahida Khandker, on the session she led in the workshop, for which participants had prepared by reading the essay ‘Life and Consciousness’ by French philosopher, Henri Bergson.

Visualizing Scales of Attention In The Living World

by Wahida Khandker

Introduction

My session was based on Bergson’s theory of consciousness as ‘coextensive with life’ as he sets out in his essay, ‘Life and Consciousness’ (Mind-Energy). The challenge was to explore some of the ideas in the text in a format that encouraged philosophical thought and discussion through activities rather than argument, and through drawing rather than writing. The starting point was this central insight from Bergson’s text:

“A consciousness unable to conserve its past, forgetting itself unceasingly, would be a consciousness perishing and having to be reborn at each moment: and what is this but unconsciousness?... All consciousness, then, is memory – conservation and accumulation of the past in the present.’ ”

The aim was to think ‘other’ (or othered) forms of consciousness, in a sympathetic, imaginative, and creative way, and to deploy contemporary philosophical and scientific studies of animal life to precipitate changes in attitude towards more-than-human species that our unfolding environmental and extinction crises demand.

Task 1: What is Consciousness?

The first task was, it could be argued, a re-invention of what is known as ‘The Molyneux Problem’ discussed by John Locke in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (originally published in 1690), which debates the nature of visual and tactile experiences of objects, and whether the two types of sensing are distinct. A man blind from birth, as the problem supposes, is taught to distinguish a cube and a sphere by touch. If the man was then made to see the objects, Locke asks, would he be able to identify them as cube and sphere by sight alone? Locke thinks not. (An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book Two, Chapter IX, Section 8)

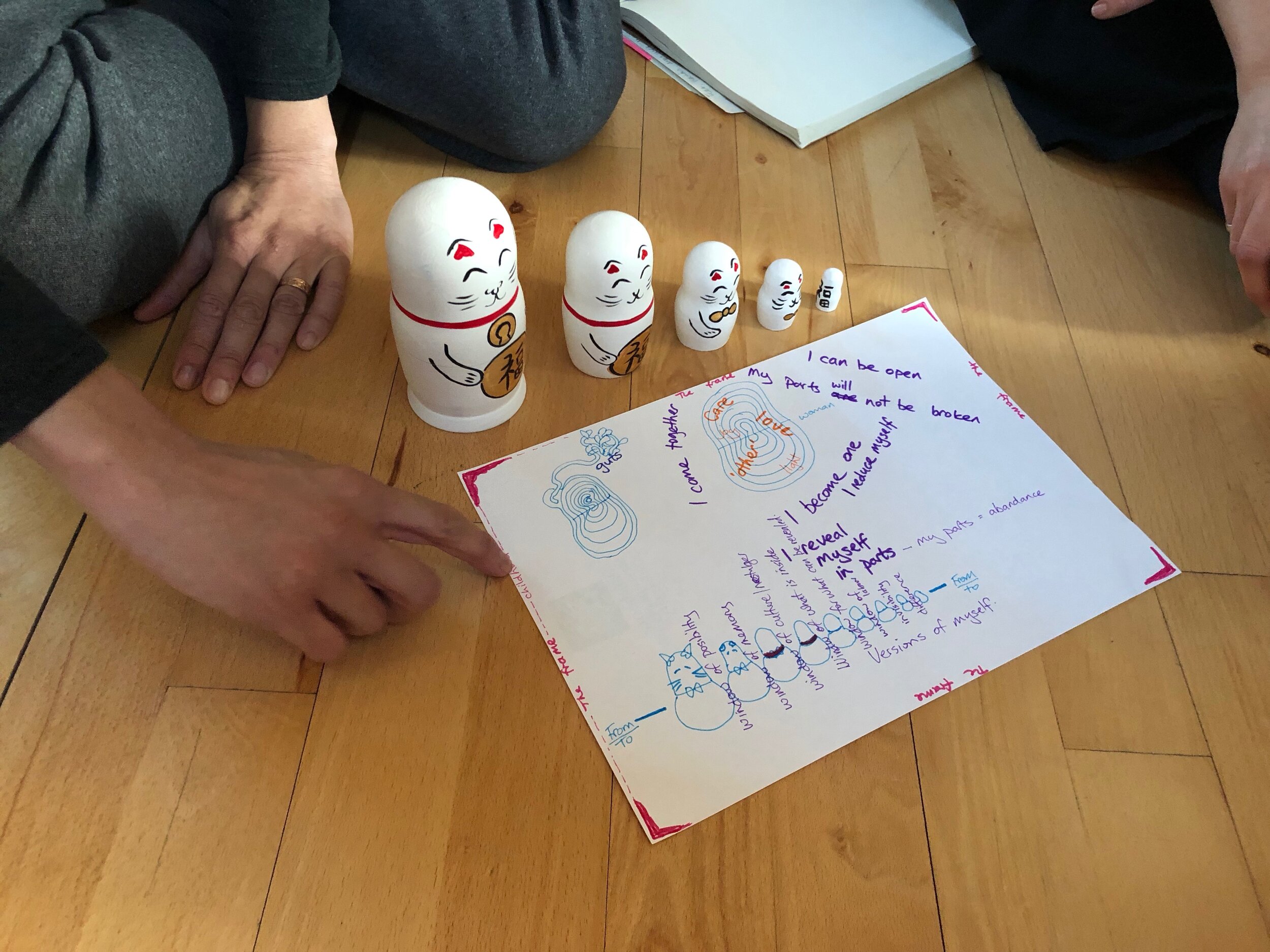

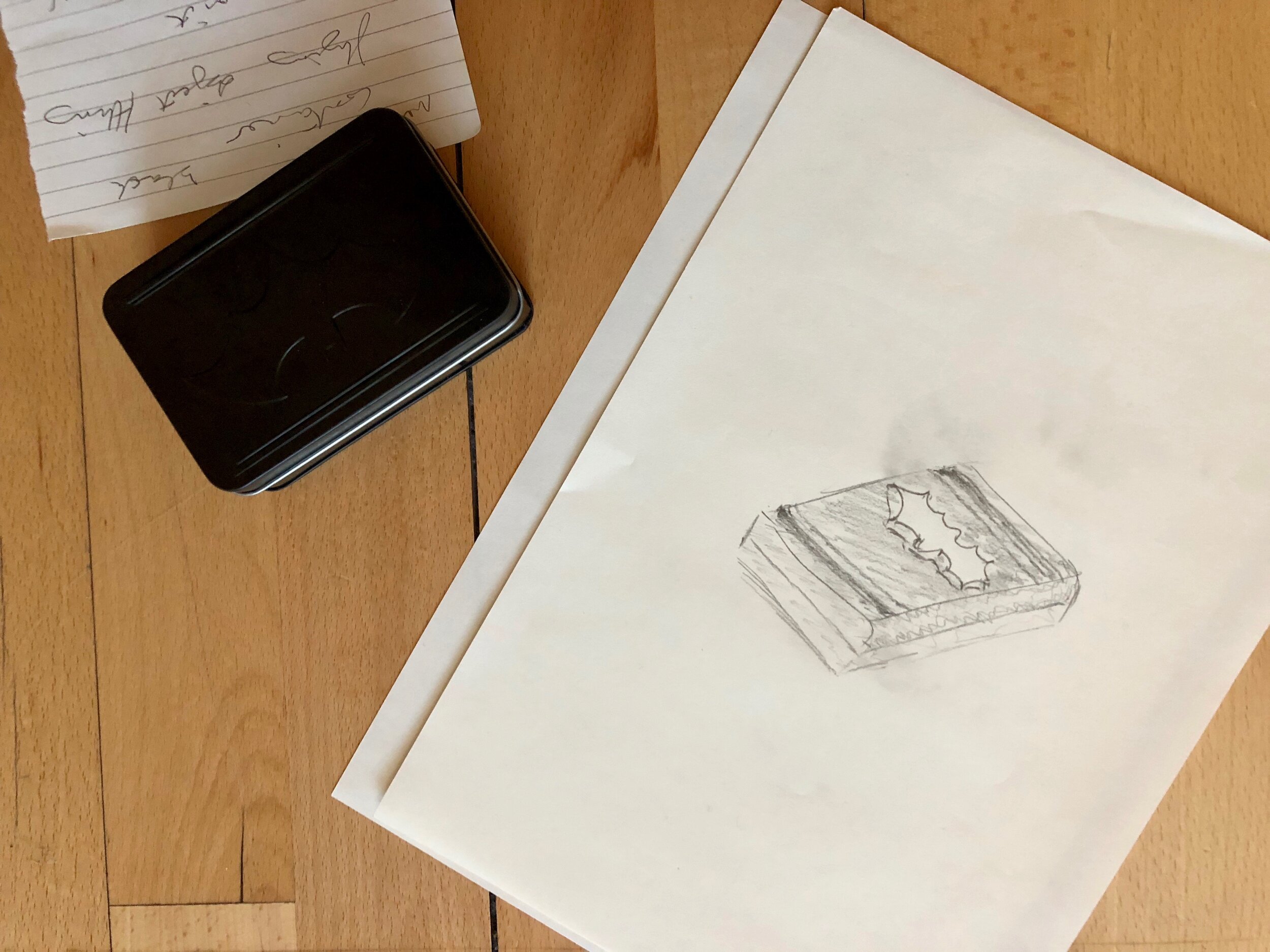

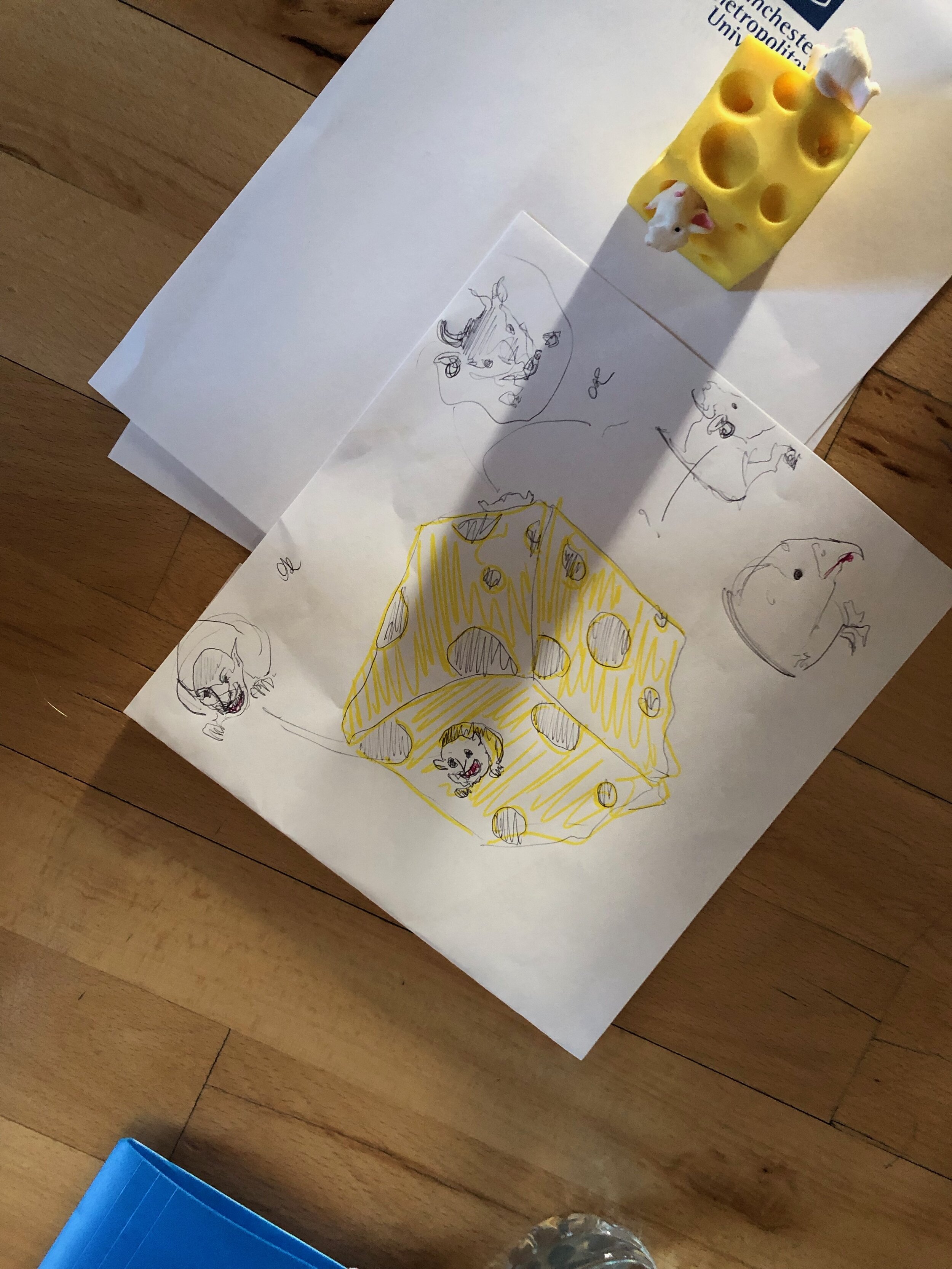

The task I designed was aimed not at distinguishing or prioritizing any particular sense, but rather to encourage reflection on the roles of sensory, intellectual, and cultural ideas in shaping how we see the world. Each small group (of 4 or 5 participants) was asked to nominate a ‘sketch artist’ who would be unable to see an object presented to the rest of the group. The group’s task was to describe the object to the artist without directly naming the object. Each artist was free to interpret what she heard, and she could choose to present her interpretation in drawings, annotations, or some combination of both.

The objects:

Each object lent itself to visual and tactile inspection. I was intrigued to see how each group would react to each object, whether they would handle or disassemble it, and what personal impressions or memories it would invoke. How much of what we see is interpretation? How well can we communicate our ideas to others who do not share our sensory, intellectual, or cultural milieus?

The results:

Each group’s sketch artist interpreted what they heard in quite distinct ways.

I was impressed with both the attempts at visual accuracy by some of the groups and the more oblique interpretations of the slowly unfurling descriptions that were built upon specific memories, on preferences, and aversions. The lucky cat nesting dolls provoked what looked like a meditation on the nature of becoming, in both images and words, in response to discussions that centred on the uses of iconography and some specific memories of past analogues of the present object in question. The task felt at its most effective when it facilitated discussion amongst members of each group and between groups on problems and questions ranging far beyond my intended aims for the session, rather than at moments when I tried to refer the discussion back to ‘the theory.’ The most Bergsonian moments of the session were perhaps the ones the least anchored to Bergson’s own text.

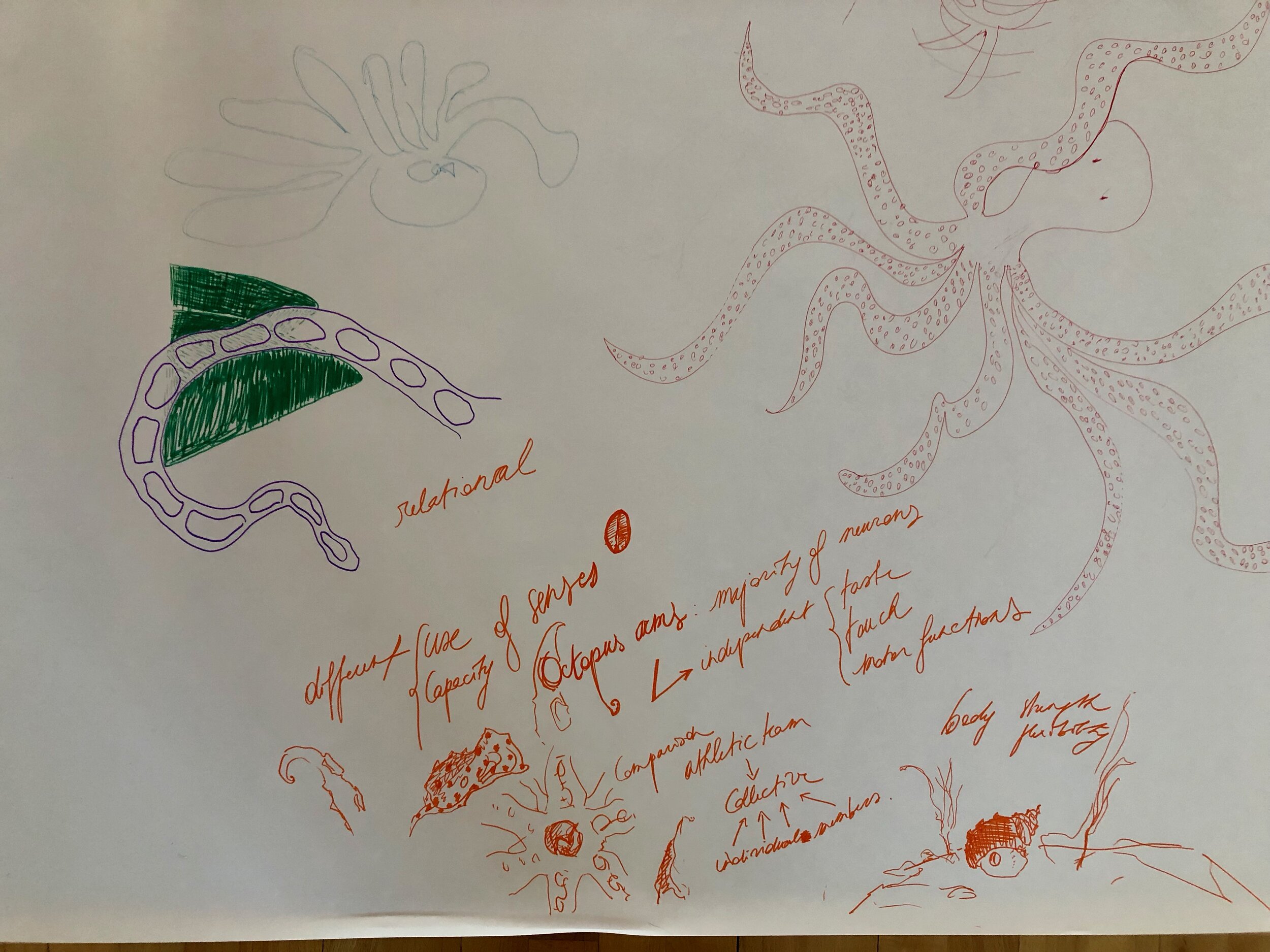

Task 2: Imagining Other Life-Worlds

The idea behind the second task, following once again the trajectory of Bergson’s essay, ‘Life and Consciousness,’ was to start to rebuild alternative ways of ‘paying attention’ to our surroundings, taking inspiration from studies of some radically more-than-human animals. For Bergson, consciousness[1] is only more diffused or decentralized in other species if we adhere to a lineage based on size and number of cells that make up an organism’s body. Thus, Bergson asks:

“If, then, at the top of the scale of living beings, consciousness is attached to very complicated nervous centres, must we not suppose that it accompanies the nervous system down its whole descent, and that when at last the nerve stuff is merged in the yet undifferentiated living matter, consciousness is still there, diffused, confused, but not reduced to nothing? Theoretically, then, everything living might be conscious. In principle, consciousness is coextensive with life. ”

Far from asking ‘What is it like to be a [bat, cat, or penguin]?,’ this task aimed to encourage reflection on multiple possible ways of sensing and remembering, in the hope that this might trouble the seemingly solid ground of human exceptionalism. Perhaps then we might be able to ‘think with’ (‘live with’) other species, with interest and care rather than with indifference or disdain.

In the resulting discussions and drawings, there was some hesitation to engage with the Bergsonian perspective offered in the text, contaminated, as it were, by early twentieth-century prejudices in favour of Homo sapiens above the ‘less complex’ array of species ‘beneath’ us. More recent research on creatures that have emerged along radically different lines of evolution, such as jumping spiders and cephalopods, such as the octopus, not only demonstrate the possibilities for evolutionary innovation in the development of alternative forms of intelligence, but they also point to the contingency of our own distinctive manifestation of ‘mind.’ ‘Life’ did not require a nervous system likes ours as a condition for the emergence of consciousness. As Peter Godfrey-Smith, in Other Minds, observes, in the more ‘distributed’ nervous system of the octopus, we see a direct challenge both to the primacy of centralized or cerebral intelligence and to the theory of ‘embodied cognition’ in which it is the organization of the body itself that ‘stores’ different kinds of act in its different parts: ‘The octopus lives outside both the usual pictures. Its embodiment prevents it from doing the sorts of things that are usually emphasized in embodied cognition theories. The octopus, in a sense, is disembodied… the body itself is protean, all possibility…’ (P. Godfrey-Smith, Other Minds, pp. 75-76)

The ideas explored in this workshop, I hope, continue to take on a life of their own.

Documentation from “On Attention: A Performance Philosophy workshop”. Photo: Laura Cull Ó Maoilearca.

Dr Wahida Khandker is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at Manchester Metropolitan University. Her research focuses on intersections between process thought, particularly the work of Henri Bergson, and biology. She is the author of Philosophy, Animality, and the Life Sciences (Edinburgh University Press, 2014), and Process Metaphysics and Mutative Life: Sketches of Lived Time (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming).

References

Bergson, Henri. Mind-energy: Lectures and essays. H. Holt, 1920

Bergson, Henri. Creative evolution. Trans. Arthur Mitchell. New York: Dover (1998).

Brendan P. Burns, Falicia Goh, Michelle Allen, Brett A. Neilan, ‘Microbial diversity of extant stromatolites in the hypersaline marine environment of Shark Bay, Australia,’ Environmental Microbiology (2004) 6 (10), 1096–1101

Godfrey-Smith, Peter. Other minds: The octopus and the evolution of intelligent life. London: William Collins, 2016.

Japyassú, Hilton F., and Kevin N. Laland. "Extended spider cognition." Animal cognition 20, no. 3 (2017): 375-395

Margulis, Lynn, and Dorion Sagan. Microcosmos: Four billion years of microbial evolution. University of California Press, 1997.

https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-beautiful-intelligence-of-bacteria-and-other-microbes-20171113/

[1] Definitions of which tend to be founded on the distinction so culturally ingrained in us that it is reason or the capacity for abstract thought, or the possession of a soul, or morality, or the ability to recognize ourselves in the mirror, and so on ad nauseaum, that separates us from other animals.